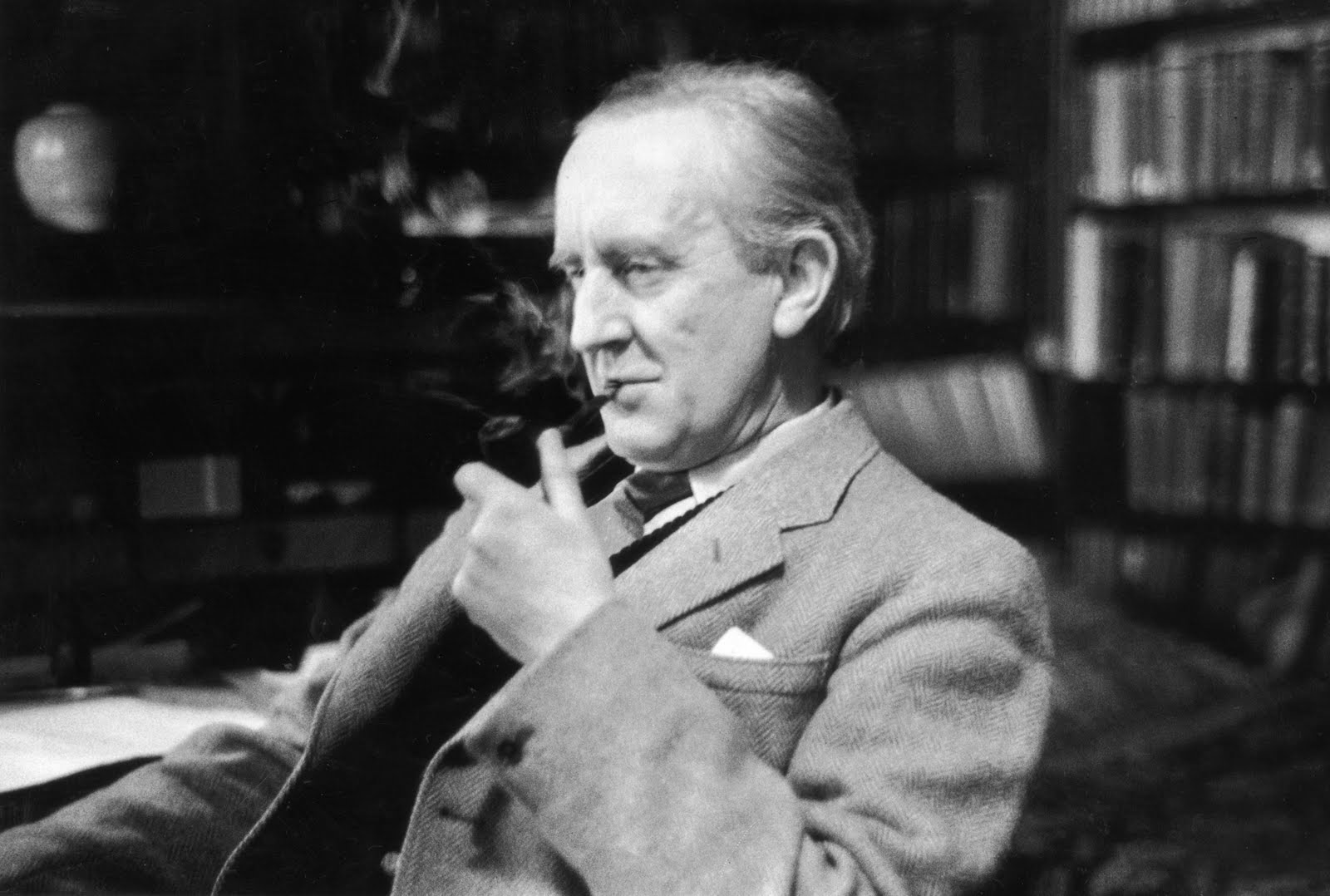

At this point, using the Dungeons & Dragons alignment system to categorize popular culture is old hat; it has made its fair share of funny memes and passed into common parlance. There are a lot of things wrong with the alignment system, but I think it remains a useful descriptive tool. In fact, I think using it as a rubric for understanding the ethics at play in J.R.R. Tolkien’s work—from The Hobbit to The Lord of the Rings and back again—can actually tease meaningful statements out of the text. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that it explains the whole point of the most contentious of all characters: Tom Bombadil.

Let’s start with hobbits. I don’t think it is particularly controversial of me to posit that the hobbit’s idyllic life in the Shire is Tolkien’s attempt to render a pragmatic utopia. Just a bunch of little folks eating six or seven meals a day, relaxing with hobbies like gardening or mapmaking, living in cozy homes and drinking with their friends. All the small pleasures in life, stretched to fill a world. I’d say The Shire, overall, could be viewed as Neutral Good. Moral people, without a need to really codify or organize things too much, but not wanting them decentralized too much, either.

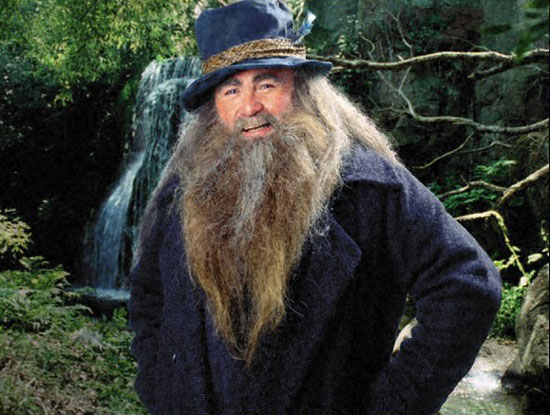

Tom Bombadil, then, is I think the enlightened, perfected version of this ideology. He is more than “Comfortable Good,” as the hobbits are; he’s Chaotic Good. Tom Bombadil is free—ahem, excuse me, I’d even say he’s capital-F Free. Tom Bombadil is a sort of bodhisattva; he expresses extremes, but those extremes are tempered by goodness. As the professor said himself (as taken from The Chesterton Review):

“The story is cast in terms of a good side, and a bad side, beauty against ruthless ugliness, tyranny against kingship, moderated freedom with consent against compulsion that has long lost any object except power, and so on; but both sides want a measure of control, but if you have, as it were taken a ‘vow of poverty’ renounced control, and take your delight in things themselves without reference to yourself, watching, observing, and to some extent knowing, then the question of the rights and wrongs of power and control might become utterly meaningless to you, and the means of power quite valueless.”

This is only half of the picture, however. The rest of Tolkien’s quote here is quite germane when we look at Noah Berlatsky’s piece in The Atlantic, “Peter Jackson’s Violent Betrayal of Tolkien” precisely because I think that Tolkien would agree with that undercutting. To wit, Tolkien’s quote continues:

“It is a natural pacifist view, which always arises in the mind when there is a war. But the view of Rivendell seems to be that it is an excellent thing to have represented, but there are in fact things with which it cannot cope; and upon which its existence nonetheless depends. Ultimately only the victory of the West will allow Bombadil to continue, or even to survive. Nothing would be left to him in the world of Sauron.”

This I think is the root of the issue, and why the alignment system works as a thesis for Tolkien literary criticism. Gondor represents a necessary evil—little e—in the form of the Law. On the subject of Good versus Evil, Tolkien assumes a moral reading from his audience. On the subject of Chaos versus Law, however, there need to be arguments made.

A quick look at Evil. We have some very clear statements on Evil in Tolkien’s work, but I’ll summarize how I view them. You might disagree with the particulars, but I think the gist of it will ring true. The Balrog is Chaotic Evil. Sure, it’s surrounded by goblins and trolls, but those are an ecosystem dragged behind in its wake. The Balrog doesn’t care about the war for the Ring, it just cares about doing random acts of cruelty, like an inverted platitude. Smaug and Shelob are Neutral Evil. They are wicked through and through, but their motives are strictly selfish. Smaug wants to lay on a pile of ill-gotten gold; Shelob wants to torture and eat you. Their motives are Evil, but ultimately personal.

Sauron—and yes, Morgoth—represent Law. Tyranny. As we see in The Hobbit, orc raids and wild packs of wargs are a problem that elves, humans and dwarves can handle…until a greater Evil starts organizing them. That is when things become truly problematic. Lawful Evil is the great juggernaut, organized and foul to the core, and all the little Neutral and Chaotic fiefdoms of the world can only either serve them or be destroyed.

Which is the “why” of Gondor, and of Rohan. Gondor is Lawful Neutral under Denethor; a strong kingdom, united to oppose Mordor…and that is necessary. Without Minas Tirith, Middle-earth would fall. No wizard could stop it, nor could even Galadriel, greatest elf left in the East, and all the elves of Lothlorien and Rivendell. For all that, Gondor is imperfect…until Good blossoms there again, with the—excuse the pun—return of the king. Aragorn is the fulfillment of Faramir’s promise; Gondor is meant to be Lawful Good, and when it becomes so, thing immediately improve.

Rohan is the question of Law, and how Good and Evil differ. Under Sauron, against Lawful Evil, you can only submit or be destroyed. Lawful Good, on the other hand, allows a flourishing of options. The Rohirrim—whether you think they are Neutral or some other alignment—are an argument for alliance, and a statement that Lawful Good allows pluralism, diversity. “IDIC,” as the Vulcans would put it. Tolkien’s Lawful Good kingdom is what allows Tom Bombadil and the Shire to exist. It is the required compromise.

Even then, we see threading through The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings the story of those hobbits. Bilbo’s mercy for Gollum is explicitly connected to the fate of the Ring. I would argue that mercy is not the same as pacifism—Bilbo spares Gollum, he doesn’t unilaterally foreswear violence, but rather sees another path and takes it. That act—along with the all-but-martyrdom of Frodo—ultimately decides the question of Good and Evil in the Third Age.

This article was originally posted on December 27, 2012

Mordicai Knode thinks about ethics a lot, to both real and fantastic questions. He is also much more a fan of Tolkien’s literary explorations of ethics than C.S. Lewis’, with the notable exception of the first two Space Trilogy books. You can find Mordicai on Twitter and Tumblr.